ARTICLE

Ceramics, Hikes, and Local Stories

23/12/2014

- Author : Roy B.

- Country of Origin : United States

- Age : 60's

- Gender :male

KAMI-ARITA

Arita is a picturesque old town, surrounded by mountains, known for its ceramic kilns and pottery shops. The Kami-Arita train station is in the midst of the historic old section of Arita, where you can see tombei walls, made of bits of pottery and bricks from abandoned kilns. The main road between the Kami-Arita train station and the Arita train station is lined with pottery shops in historic buildings.

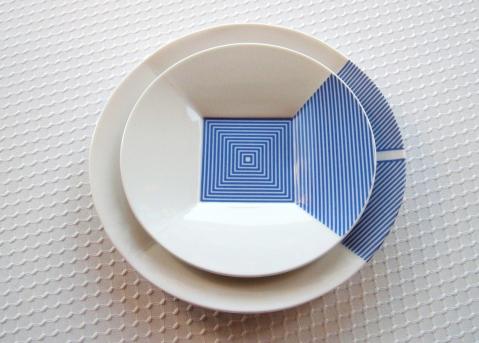

Along this route, at Arita Porcelain Lab, ceramicists with deep roots in the history of Arita experiment with new contemporary designs, some in non-traditional colors. I find myself surprised by the cacophony of pink, green, light blue, silver, and gold in their showroom, with names like Japan Blue, Japan Cherry, Japan Snow, Japan Autumn, and Japan Tea. I picked up a few items (mostly their older designs) from their 50%-off outlet store, and bought some bright-colored cups (bright pink from their Japan Cherry collection and silver from their Japan Snow collection) from their main store. I told the cashier I'd seen the proprietor smashing plates in his You Tube video (which you can see at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NXyzARJp-Qc). Actually, I'm not sure that "told" is the right verb--her English was limited, and my Japanese is just awful. My communication was mostly gestures of smashing plates and the English words "You Tube." She showed me a magazine photo of the proprietor, so I know she understood me.

My next stop was the Touzan Shrine, which is notable for its ceramic torri. Behind it, and up the hill, is an obelisk which is a memorial to Ri Sam Pei, a Korean who was brought to Japan, perhaps not voluntarily. He helped the Japanese refine their ceramics skills, and in 1616 he discovered a kaolin deposit in Arita. Kaolin is an ingredient in porcelain, so he is considered responsible for the creation of the porcelain industry in Arita. There is a plaque at the base of the memorial, placed by the local Korean-Japanese Friendship Society, that recognizes his importance in the history of Arita and specifically its porcelain industry.

A little further down the road to Arita is the Koransha porcelain shop and museum. Koransha is an old, well-established kiln. Their shop and museum are in a two-story building with a Western-style antique curved wooden staircase, something you would expect to find in a Victorian building.

ARITA

Arita is my favorite town for shopping for ceramics, with its Wholesale Ceramics Plaza just a 20-minute walk from the train station. There are 23 stores around a central plaza, and they sell both traditional and modern designs. Many items are 30% off the posted prices, and there is a tremendous variety of ceramics available. I can easily spend two days shopping there! The larger stores are on the western side of the plaza.

Sometimes, the store proprietors will offer you a cup of tea, or if you look American, perhaps a cup of coffee. At one store, my purchases plus tax came to 3,804 yen. They asked my permission to knock four yen off the price because the number four in Japanese sounds like the word for death, and the cashier didn't want to burden me with a bad omen. For the same reason, you won’t find anything in sets of 4—sets of 5 are more typical.

To get to the Wholesale Ceramics Plaza from the Arita train station: As you leave the front of the train station, walk straight ahead (south) one block, then turn right (at the Garo and Sausalito shops) and proceed until you get to the gas station. At the gas station, turn right and walk under the railroad tracks. Continue past the SuperWest supermarket (or stop in for a snack!). At the next traffic light, turn left, go one block, and then turn right. It's about a 20-minute walk from the train station.

Also of note is the Genemon Kiln, just north of the Ceramics Plaza. Genemon is one of the oldest kilns in Arita, and both its quality level and prices are way out of my league. I was amazed at the brightness of the white porcelain, the intensity of the hand-painted colors, the quality of the brushwork on the pigmented areas, and the sharp separation between the colored areas. You can even watch the ceramic artists decorating the porcelain.

I timed my trip to coincide with the annual autumn Sarayama Kunchi (best called O-Kunchi, the formal polite form) festival in Arita. (Traditionally, it has been held on October 17, but in 2014 the town experimented with switching it to the nearest weekend.)

In the days before the festival, a group of traditional dancers arrive in the Wholesale Ceramics Plaza, stopping in front of sponsoring stores to perform. At the end of each performance, the store proprietor hands an envelope with their sponsorship contribution to the head of the dance troupe. A flat-bed truck with drummers circulates through town during the afternoon and evening, stopping to perform at each of the sponsoring businesses. The drums are mostly ceramic, and there are also ceramic bells on the truck that are part of the performance.

On the day of the festival, there was a full afternoon of parade events along the street that runs from the front of the train station. The town's mascots appeared in the early part of the parade. The first mascot is a young boy who wears an inverted blue and white striped ceramic bowl on his head as a hat. There is also a newer mascot named Cerami, with flaming red hair to symbolize the heat of the kilns, created for the 400th anniversary of porcelain manufacture in Arita, which will occur in 2016. (Cerami was unveiled at the Arita Town Office in April 2013, when Town officials issued him a Special Resident Card with his picture.) After the mascots made their appearance, there was a small group of young women doing a local dance, using pairs of small ceramic plates as castanets. Groups of costumed school kids did various dances and marches, sometimes prompted by their teachers giving directions from the sidelines, and watched attentively by their grandmothers, who sat in rows of chairs along the street. A group of men carried a portable shrine decorated with stacks of ceramic bowls. There was a historical pageant with costumes from the last four centuries. I was impressed with the graphic designs and colors of the costumes. The events culminated in a massive plate dance, involving all the adult participants from the earlier phases of the parade, that reminded me of those old Hollywood movies with big dance numbers. But this was reality--there were a couple of embarrassing instances of plates being dropped. A volunteer stood by with brush and dustpan, and there were plastic bags at the ready to tidy up the evidence.

One of the marchers reminded me that the 400th anniversary of pottery-making in Arita is just a few years away, in 2016. Another invited me to join the massive community plate dance at the end of the festival, an honor I politely declined. One told me that he works for a company that makes pigment for underglazes from barium, cobalt, silica, and feldspar. Several asked where I was from.

Although there was a police presence at the festival, there wasn't much for them to do other than direct traffic. The only other police activity I saw involved a women who had the bad luck to park her car in a small parking lot off the main street, in the area that was now closed to traffic for the parade. She described her plight to the police, and when there was a pause in the parade, they guided her out of her parking place so she could make her escape.

Amazingly, when the big plate dance ended, almost everyone quickly disappeared (except for a few kids and food vendors who lingered). There was no litter in the streets. I walked over to the food vendor area and asked the fried chicken vendor for a medium cup of fried chicken. He handed me a cup and pointed to tongs for me to use to fill it. When I was done, he said "more, more" and added more to the top.

The Kyushu Ceramic Museum is on a hill which is a short walk south of the Arita train station. It's worthwhile, and admission is free. On the upper floor, there is a large exhibit showing the history of ceramics in Kyushu. There is also a large porcelain clock with ceramic gears and moving dolls. It chimes every half hour, quite a show! The lower floor consists entirely of items donated by a couple who collected ceramics from the area for many years. The museum had examples from the 1700's of simple geometric designs--if I hadn't known when they were made, I would have described them as modern.

Arita Porcelain Park is located about an hour’s walk south of the train station, about halfway to Hasami. As you enter Porcelain Park, the first thing you see are several enormous chained-off unused parking lots. Then, off in the distance, there's an almost-full-size replica of the facade of the Zwinger Palace of Dresden, Germany. There is also a sake brewery on the property. There are many buildings in old German style, most of which are unused and deteriorating. The replica of the Palace includes a museum of European and Arita porcelain, and an area used for special events. At the rear of the Palace, there is a large and well-kept garden. A few of the other period buildings are used as porcelain shops and a paint-it-yourself pottery studio. And there is a large gift shop, stocked with local foods, ceramics, and other omiyage items, next to a tour bus parking lot. There were many Japanese tourists, mostly middle-aged, in the big gift shop, and a smaller number of visitors wandering on the grounds. According to one of my guidebooks, Porcelain Park was built as a theme park, never attracted the projected number of tourists, and eventually went through a bankruptcy.

HASAMI

Hasami, a small town in Nagasaki Prefecture, is about a 2-hour walk south of the Arita train station. (Hasami does not have rail service.) It was a long walk, including a hill, but the route is not complex, so there’s little risk of getting lost.

Amazingly, there were sidewalks for the entire route, which included some very rural areas. In Arita, the street furniture included glass exhibit cases with pottery inside. Then it was over the river, through the hills, and under the Nishi-Kyushu Expressway. I passed some rice fields that were being harvested.

From Arita Station, just walk south on the road that dead-ends at the station, then turn left to Route 35, then right to Route 4. Route 4 takes you south past the ceramics college (stop in to see their exhibit of student works in the front lobby, and try to allow a few extra minutes to linger at the ceramic art display stands along the road), past the access road for Arita Porcelain Park, past the Arita-Hasami interchange for the Nishi Kyushu Expressway, and then to Hasami. A few blocks after you pass Family Mart, look for the sign pointing the way to Hasami Ceramics Park. Turn left, proceed past Hasami Ceramic Park, and you will eventually get to the Hakusan factory store.

The Hakusan company had been producing traditional porcelain in Hasami for generations. During the postwar economic boom, its President heard a prominent industrialist say that design is the future. So, in 1956, Hakusan set out to hire a designer and got Masahiro Mori. Mori created modern minimalist designs which Hakusan mass-produced.

Everything at the Hakusan factory store is 30% off the usual price, so it was worth the walk! As I was checking out, the salesclerk noticed a small scratch on one of the items I was buying. I could barely see the scratch. She made a couple of frantic calls, and I could hear much commotion in the stockroom. Another employee, with better English skills, arrived to break the news to me. After much apology, she explained that they cannot sell an item with any defect. And she remembered me from my visit two years ago!

Retracing my steps back to Arita, I stopped at the Hasami Ceramics Park. The park has a colorful wall made of ceramic pieces, outdoor exhibits, and a huge shop that carries local ceramics from a variety of kilns. I was able to find products there from shops that I didn't have time to visit.

On my walk back to the Arita train station, I must have looked as tired as I felt--a woman with a car full of kids had her daughter offer me a ride (a teachable moment in her child rearing?). I declined the offer since, by then, I was close to the Arita train station. People here really do look out for foreign tourists!

OKAWACHIYAMA (IMARI)

Today, I went to Okawachiyama, "the village of the secret kilns," on the outskirts of Imari. It would probably be an easy trip by car or bus, but I took the train. From Saga, using a Japan Rail Pass, the route is the Karatsu line from Saga north to Karatsu, then the Chikui Line southwest from Karatsu to Kami-Imari, then a 1 1/4 hour walk to Okawachiyama. Including the transfer time in Karatsu, the rail trip takes 2 1/2 hours each way, so it was a lot of travelling. I was glad I had researched the departure and arrival times of each train, and the names of all the stations along the way. These are rural train lines, and stations typically have just one English sign, which can be easy to miss. You can use www.hyperdia.com to get schedules and a list of all the stops on each line. Hyperdia might have you make the transfer at the tiny rural station at Yamamoto, but it’s easier to go a little further and make the transfer at Karatsu--it won’t take you any longer, and the station facilities at Karatsu are better.

Since I had a 40-minute wait between trains at Karatsu, I walked across the street to the Arpino Building, which has a ceramics shop that also includes some exhibition pieces. The classic Karatsu style is brown with a thin black plant design.

From the Kami-Imari station, take the paved path north and keep going in that direction after the path joins a road. The road crosses a river. After a short distance, turn left where the road ends at an intersection with a major road. After one block, turn left to Route 202. Then turn left to Route 26, and right at Route 251. (This route takes you on a semi-circle around the train station, and then on a long walk along Routes 26 and 251.)

Despite the complexities of the logistics, the walk from Kami-Imari station to Okawachiyama is quite beautiful. The first highlight is actually an Idemitsu gas station, where you make your left turn to Route 26. The Idemitsu station has two concrete walls decorated with inlaid ceramic plates in classic local designs.

Beware, there is only one convenience store on this walk, so don't pass by the 7-11 thinking that a Family Mart must be just around the bend. The last part of the walk takes you through a scenic secluded valley, with rice fields and views of forested mountains. Pity the tourists on the tour buses that pass you; they are moving too fast to really experience the beauty of the valley. The Nabeshima Clan established kilns in this valley because it was easier to provide security for the Korean potters (who were brought here under circumstances that may not have been entirely voluntary) and their glazing secrets. At Okawachiyama, there are bridges decorated in ceramics, historic kilns, and many ceramics shops.

KAGOSHIMA

On my first day in Kagoshima, I took the ferry to the Sakurajima volcano, which used to be an island, but the last big eruption turned it into a peninsula connected to the other side of Kyushu. The ferry runs 24 hours a day! After reaching Sakurajima, I took a walk along the Nagisa Lava Trail. The first thing I saw was smoke billowing out of the top of the volcano! Oddly, there was none of the sulfur smell I remember from the volcano in Hawaii. Ah, this is Japan, and that sulfur odor would probably be a breach of etiquette. The next thing I noticed was a sign for a Public Foot Spa. Intrigued, I investigated, and there it was--a row of seats along a pool of hot dark water from the volcano! I tried it, and it was very relaxing! As far as I could tell, this public amenity is available all day and night!

Things seem a bit less formal here than in Tokyo, and the region (originally known as Satsuma) has always been independent-minded. My hotel let me into my room an hour before the official check-in time, a breach of the rules that would not be permitted in Tokyo! The Museum of the Meiji Restoration is about the role of Satsuma in opening Japan to Western technology and culture. In 1865, the Satsuma clan illegally sent a group of its best students to England to study British technology, culture, and language. At the time, contact with foreign nations was strictly prohibited by the national government. The museum has a short film about their experiences--the long trip in huge ships that were far larger than anything they had seen in Japan, the technology of piped natural gas that could light an entire city, and industrial technology far beyond what existed in Japan. They also saw how badly the British colonists treated the people in the Asian countries they dominated, throwing coins from their enormous ships to the scrambling natives in the bay below. It's hard to imagine the pressure these students were under--their trip was completely illegal, they would have been executed by the Japanese authorities if they had been caught, and they had the responsibility to quickly learn English and bring Western technology back to Japan. After their return to Japan, most of the students took on high-ranking positions in government, education, and the emergence of industrial technology, and become prominent in the Meiji era. There's a statue of the students in the plaza in front of the main train station in Kagoshima.

MOJIKO

Kitakyushu is the 13th largest city in Japan, but, aside from Space World, it gets hardly a mention in my collection of guidebooks, maybe because it has heavy industry, including a large steel plant. Surfing the internet, I happened to find a guide map for Retro Town Mojiko. Retro sounded intriguing! Mojiko is literally at the end of the line, that is, the Japan Rail Kagoshima Line. From Hakata, it's only about 45 minutes by rail if you do the Hakata to Kokura portion of the trip by Shinkansen. Between Kokura and Mojiko, there is only one choice, the slow train. Mojiko is located at the Kanmon Strait which separates the island of Kyushu from the island of Honshu. According to myth, at one time, the two islands were connected, but at a particularly strategic moment, the islands separated and the strait was formed. Think Red Sea. Mojiko had strategic military importance, so it was the focus of several wars and fights over whether this part of Japan would be open to foreign trade (a theme that also affected Nagasaki and Kagoshima). Mojiko had an important role in the banana import market, which anyone who has seen perfect melons selling for $10 to $50 in Japan's supermarkets will appreciate. Mojiko also became an important terminal for both the railroad and cruise ships. So it's full of Meiji-era Western-style buildings, mostly built in grand style between 1910 and 1920. There's a nice little railroad museum, a couple of small shopping plazas, and a new hotel with a striking modern design. The view of the waterfront and the bridge across the strait is just beautiful.

KOKURA

I just can't pass up a shopping mall with an exotic name, and Japan has so many of them! When I heard about the Cha Cha Town shopping mall in Kokura, I just had to go there. But first, a bit of history. Kokura is an industrial city, now part of the consolidated city of Kitakyushu. During World War II, Kokura was designated as the target for the second atomic bomb, but on the day of the attack, it was too cloudy in Kokura for the pilot to see exactly where the bomb would land, so they went to Nagasaki instead. There is now a term called "Kokura luck," when you avoid tragedy by mere chance. Cha Cha Town is about a 10-minute walk southwest of the Kokura train station. (The main street in front of the train station is named Heiwa Dori, which translates to Peace Boulevard.) Cha Cha Town has a colorful neon-lit entrance, and the neon lighting theme extends to its Ferris wheel. Inside, there is a small Uniqlo store and a Daiso 100-yen store with a huge selection. But no cha cha music; they are really missing an opportunity!

MINAMATA

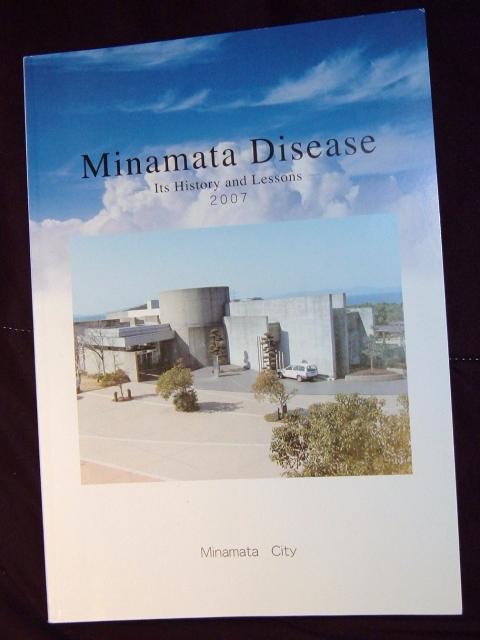

It's raining heavily, and I am on the way to the Minamata Disease Municipal Museum. Kyushu is justifiably proud of its newly extended Shinkansen train line, which now runs all the way to Kagoshima-Chuo. Minamata is a small city on the coast between Kumamoto and Kagoshima. The Shin-Minamata station is ultra-modern, with safety gates to keep passengers away from the edge of the tracks unless a train is present. What a stark contrast to the adjacent Hisatsu Orange Line, a little private railroad that will take me from Shin-Minamata to Minamata. The Orange Line doesn't really have a station here--you just walk across the train track to get to the boarding platform.

In the rain, it seems like a long walk from the Minamata train station to the museum. Fortunately, I have figured out how to wrap everything in my backpack in plastic bags, so I don't have to worry about important things getting wet. As I approach the museum, I find myself in an enormous seaside park that seems strangely large. It's a long way from the park entrance to the museum. By the time I get to the museum, it's raining hard, and I'm happy to get under a roof! The museum staff invite me to watch a film in English about Minamata Disease. Meanwhile, a large group of Japanese schoolchildren are listening to a presentation from an elderly man.

In 1908, the Chisso Company opened a chemical plant in Minamata, a seaside fishing village, initially manufacturing fertilizers. In the 1950's, in the postwar economic expansion, Chisso vastly expanded its production of acetaldehyde, acetic acid, and chemicals used in the plastics industry. The acetaldehyde synthesis process used mercury sulfate as a catalyst. Small amounts of methyl mercury were created as a by-product of this process. The methyl mercury was released into Minamata Bay for many years. The mercury accumulated in fish and shellfish from the Bay, and people who ate large quantities developed mercury poisoning, with seizures and severe neurological symptoms. People who couldn't afford much rice could still fish in the Bay, so they were most at risk. The disease was seen early in cats, which would show signs of seizures.

Chisso had evidence that its waste water was causing these symptoms, but continued to contaminate the Bay for a decade. Eventually, the affected people sued and, after many years and many small victories, won increasing amounts of compensation. In 1968, Chisso finally stopped releasing methyl mercury into the Bay. The Chisso factory is still in operation in the center of town. The town, still struggling to emerge from the stigma, is finding a new identity as a community of environmental stewardship. It would seem to be a simple story of an evil chemical company, brought to justice after years of courageous community organizing against pollution. But reality is more complex.

In the 1950's, there was tremendous optimism that economic expansion, modernization, and the chemical industry would bring wealth to Japan and to Minamata. Local fishermen noticed that boats docked near the Chisso waste flow never developed barnacles or fungus, and began docking their boats there to reduce the need for maintenance. Before the mercury connection was known, many people thought that Minamata Disease was infectious, and its victims were shunned by their neighbors. Even when the cause of the disease was understood, people from Minamata faced job discrimination elsewhere, and were deemed to be unsuitable marriage partners. As the mercury pollution connection became clearer, townspeople became divided against one another. There was fear that those affected by mercury poisoning could force Chisso into bankruptcy and destroy both the town's economy and the source of compensation payments. There was suspicion that people were exaggerating their symptoms in order to get compensation, even jealousy at the newly improved economic status of the compensated victims. The Chisso factory is still in operation in the center of town. The town, still struggling to emerge from the stigma, is finding a new identity as a community of environmental stewardship.

Early in the history of Minamata Disease, the Chisso Company clinic doctor fed a cat some food mixed with effluent from the Chisso factory, and the cat developed the neurological symptoms characteristic of Minamata Disease. If you were in his position, how far would you go with this information? Would you act to shut down a town's only industry based on an experiment that involved only one cat? Would it be enough to report your findings to your superiors and let them decide what to do?

In the midst of this emotional chaos, there are inspiring stories of forgiveness and reconciliation. The museum documents stories of neighbors who apologized to victims for shunning them, victims who responded by forgiving their neighbors, and victims who have gone one step further to forgive the people of Chisso. Some have even organized for an international treaty restricting the use of mercury in gold mining and industrial processes, so that people in poorer countries will not repeat the experience of Minamata.

It was still raining hard when I left the museum. As I passed the parking lot, I saw a car waiting, and the driver, one of the museum staff, offered to give me a ride to the train station. I said something about growing up in New Jersey, where we were surrounded by the chemical and pharmaceutical industries, and believing that chemistry was the solution to so many problems. He told me that the mercury wasn't really gone, it had been covered up with landfill and capped so it wouldn't be a danger and so the bay water would be clean. (So that was why the park was so vast--it needed to be large enough to hold all the mercury-contaminated Bay sludge.) He asked me if I had any children, and said that he had two. He said, with some excitement, that the museum was preparing for a visit from the Emperor later that month. Then he told me that he had grown up in Minamata, moved to Tokyo to go to university, and then realized that he belonged back in Minamata. "I love this town," he said. And I think I understood why.

CHIRAN

The Peace Museum of Kamikaze Pilots in Chiran is a deeply sad place, filled with copies of the last letters the pilots wrote before their fatal missions, headbands they wore, messages from their colleagues, and personal effects. Most of the photos of the pilots show smiling faces, even in photos taken the day before their missions. There were little sticky notes on some of the photos--all in Japanese, some handwritten, some printed. I wonder what they said--perhaps "I knew him" or "He was from my town." There were final letters from the pilots--many thanking their mothers for raising them, one encouraging his fiancé to forget him and live in the present, another asking his children not to be jealous of other children who have fathers. One pilot wore his fiancé’s scarf in his final photo.

There was a story about a Japanese pilot who crashed into an American warship, killing himself in the process, but merely damaging the American ship. One of the American men on the ship saved the dead airman's headband and, years later, with the help of a Japanese newspaper, returned it to the man's family in Japan. The headband was full of good wishes from the pilot's friends at school, and is now on display at the museum.

Another story was about a Japanese-American born in the United States who was in Japan when the war broke out. The other pilots were always a bit suspicious that he might be a spy. His two brothers were in the American army, serving in Europe.

The English audio narration provided a Japanese perspective on the roots of the Pacific War (what we call World War II), describing it as Japan's effort to stop Western powers from colonizing Asia so that Japan could enter into mutually beneficial relationships with its neighbors in Asia.

There was also a story about how the pilots were cheerful on the outside, but the night watchman noticed that, on the night before their missions, some of the pilots would pull their blankets over their heads and cry, and when the girls from the local school came to tidy up the pilots' huts, they noticed that the pillows used by the pilots who had gone out that day were wet with tears.

One of the museum visitors was an elderly man who lingered at every photo display, perhaps looking for people he knew. Another was a young woman who might have been imagining the world of the woman her age whose scarf was in that photo. Another was a young Japanese man wearing a denim jacket with a faded American flag patch on the shoulder. And there were a few small children who were simply enthralled with the big planes. And that couple from Kumamoto who made sure I got out at the right bus stop--what were they feeling about their excursion to Chiran?

![Kyushu Tourism Information [ Japan ]](/blogcontest/img/common/bnr_onsen_island.png)